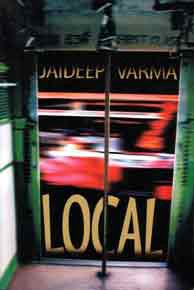

Jaideep Varma's novel, Local, tells the story of an advertising copywriter named Akash Bhasin who has moved to Mumbai from Madras after a divorce. To get away from his angst-ridden life — numerous personal, emotional, and a few professional problems — he decides to give up his costly PG digs and live his nights on Mumbai's suburban western line trains. The train is the only place where he can forget the chaos and stress in his life. The train's continuous movement and rocking motion are the only things that relax him. Seeking this restful feeling all the time, Akash decides to make the trains his home.

Jaideep Varma's novel, Local, tells the story of an advertising copywriter named Akash Bhasin who has moved to Mumbai from Madras after a divorce. To get away from his angst-ridden life — numerous personal, emotional, and a few professional problems — he decides to give up his costly PG digs and live his nights on Mumbai's suburban western line trains. The train is the only place where he can forget the chaos and stress in his life. The train's continuous movement and rocking motion are the only things that relax him. Seeking this restful feeling all the time, Akash decides to make the trains his home.Local is thus the story of Akash Bhasin's schizophrenic existence. Through the day he works in an ad agency creating wants for others, while in the evening he chooses to surrender himself to the "rocking homelessness" of a train, shuttling back and forth between stations till morning. The novel is largely a story of these two contrasting worlds: a competitive ad agency where colleagues try their utmost to best others, and a local train where everyone standing was "propped up by his fellow travelers." Local is the tale of the people who inhabit and move in and out of these two worlds.

We mostly follow Akash through his days at work in the agency and nights in a train compartment, experiencing either of the worlds through his observations and experiences. Varma punctuates this straight narrative with short stories — vignettes of the other people from either of Akash's worlds, who too seem to be living lives of quiet desperation. I personally feel it this narrative commingling of short stories within a bigger "grand" narrative that is Varma's greatest achievement as a writer in his novel. This narrative structure allows him to not only tell us Akash's story, but also expand his canvas sufficiently enough to bring in the perspectives and lives of other characters who in their own way tell us about Mumbai in all its different facets and colors.

It is in these short stories that we come to know more about numerous interesting characters: the balding, pot-bellied, former taxi-driver Subhash who believes he can be a model, Dr. Shenoy who takes local anesthesia to overcome his stutter and who lives as a paying guest in order to pay the loan for a flat he has bought for the woman he loves, the attractive and smart Sabina who, in order to gain the upper hand in her marriage, conspires with a friend to seduce each other’s husbands, Neha who finds about the infidelity of her husband and makes a desperate attempt to get even with him. We also meet a "professional defecator" and two old, unwanted people: one who still tries to make the world bend to his will, the other who tries to find happiness and dignity within her. Through these stories Varma paints a city that is trying to fight loneliness and come to terms with dysfunctional relationships, a city where its people are trying to adjust to the gap between dreams and reality, success and failure.

Interestingly, these vignettes stand-out and away from the main narrative of the novel in yet another way. While Akash is acquainted with them, he is not privy to what is happening in their lives or the crises they are facing. Thus we readers also get only enough of a glimpse into their lives to find them interesting, but rarely do we get to know any of the characters intimately. The different characters leave an impression on the reader but nothing more.

I don't know if Varma deliberately was trying to create this effect, or if I am reading too much into the novel's narrative. These stand-alone vignettes actually feel like coming across people during a railway commute. What they do and talk, might seem interesting, but we never get to know them better because they get off the train when their station comes. We are not privy to the rest of their lives. Somebody else comes in and we glimpse at yet another life in passing. It's also a bit like seeing and knowing all the different stations and platforms on a long commute — they are familiar but only in passing.

Of the two worlds depicted in the novel, Varma is at his best when he is writing about the goings on in an ad agency and the people who make up that world, probably because he is so familiar with it. The character of the brilliant and driven Bibek (who in the end leaves to find out where deleted e-mails go) is a gem.

Surprisingly (given the title of the novel), it is Varma's world of suburban trains that disappoints a bit. Most of what Varma writes about the life in a train is very observant, very detailed . . . but it remains at that level. I may be biased in this reaction — I spend an average of four hours daily commuting by train from my home to my office (most of my reading, this novel included, happens during my commute.) — but I felt Varma really gives no special insight into the life of commuters on a train. We, of course, get the stories of the kind we are now accustomed to read in the mainstream press: women shelling peas and cleaning other vegetables for their family's evening meals, a retired gent traveling with his cronies so that he can play cards with them, what happens when rains halt trains, etc. But I expected these sections to go a bit beyond journalism and give us something more. It's a bit like reading the title and the blurbs and realizing here's a premise that's intriguing and rich in its possibilities but finding that it didn't live up to your expectations (the fault entirely is mine). Of course, I may be cribbing about something that I am just too familiar with. A reader used to the ad world might feel similarly about what Varma has written about the ad world — the depiction of which I found to be excellent.

The novel is otherwise quite interesting and has a confident voice. It's a tale that's amusing and witty in parts, and in many places, poignant. Local shows us a part of the Mumbai experience very well — the commute, the alienation, the dysfunctional relationships, the hope and the spirit unique to its people — and there will be many readers who will be able to relate not only to numerous experiences described in the novel but also to many of the insecurities and frailties shown by Akash and the other characters. There are many "Mumbai as I have experienced it" moments in the book. But the book's appeal surely transcends its setting. While Local is undoubtedly a "Bombay Book," it can be read with much interest by people anywhere for ultimately the book is more about human experience than it is about a setting. The "Local" is only incidental to the plot.

Whenever an Indian publishes a novel in English, we all like to measure and weigh its worth against other authors and see how it stacks up against a Rushdie, a Mistry, or a Ghosh (and of course, see if it is "international" enough). We can't help it, it's just one of the things we do. Well, Local and its Mumbai is very unlike the one described by a Rushdie. There is nothing exotic or romantic about Varma's Mumbai. As I said earlier it is very much about Mumbai as you and I experience it — its contemporary and it is about the kind of people that we run into everyday. Local is also not high art nor is it in the pulp or the bestseller mode — and it doesn't try to be either. It is not intimidating nor is it kitschy. Local's triumph is that for many of us it is about an experience and a setting that is recognizable. And it is for this reason that I would recommend that this book should be read.

Update:

I exchanged a few emails with Jaideep Varma, regarding what I had posted about his novel Local. In my review I had pointed out that I was a bit disappointed by his depiction of the world of suburban trains: that it was merely observant but really gives no special insight into the life of commuters on a train. In his email, Jaideep Varma has clarified and presented his perspective on why he has treated the train sections of his novel in a journalistic style. His explanation should help readers understand the thought and reasons that writers put behind getting a section (or their entire work) to have just the effect that they want it to have on their readers.

I have, with his permission, excerpted from his email below. I have edited out parts from his email which referred to other works or are not really essential in understanding his point of view.

Your main criticism, [. . .] that the train parts are just journalism is factually not incorrect, it's just that you may have missed the point a little bit [. . .]. See, Akash is living the life of a participant during the day and an observer during the night. What he takes in by way of trying to kill his feelings on the train can only be taken in in terms of details that he notices on the train and in details of how he feels on a conscious level. The point of the main narrative is how Akash changes, not the people on the train.

[. . .]

If this was non-fiction, then that would be a more valid criticism than it is here, in my opinion. Because my responsibility as a storyteller here is to the story of Akash and his evolution, not to the city of Mumbai and its inhabitants. That is merely the setting. You see what I mean?

[Referring to another book . . .] did you get great insights in the chapter on the local trains? Do you see that [commuters helping each other] more often than commuters blocking the doorway to prevent others from coming in? You tell me. So, why are you expecting great insights about train life here - because of the title? (see, i understand why this would disappoint you - not finding things that you didn't know - i'm just trying to explain why that was not my point).

technorati tag(s): Book Review: Jaideep Varma's Local

No comments:

Post a Comment